Neolithic source population: Iranian farmers

G2b, known as G-M3115 on the phylogenetic tree, is a Y-DNA haplogroup with a high diversity among modern people in the Caucasus and the Middle East. It likely arose among Mesolithic West Eurasian Hunter Gathers living close to the Zagros Mountains around 20,000 BCE.

Ancient skeletal evidence supporting this point of origin include:

- Sample I3882 of Zawi Chemi Shanidar cave, northern Iraq, C14 dated 13,101-12,429 BCE. The owner of this tooth fragment was a carrier of the cousin clade G2a1 (Lazaridis et al 2022).

- Sample WC1 of Wezmeh cave, Kermanshah province, western Iran, C14 dated 7455-7082 BCE. The owner of this phalanx (toe) bone was a carrier of the descending clade G2b2a (G-Y37100) and an early member of what’s often called the Iranian Neolithic or “Iranian farmers” (Broushaki et al. 2016).

Bronze Age spread of G-M377

All identified living carriers of the Y-DNA haplogroup G2b in the region of South-Central Asia are carriers of the descending lineage G-M3115 < G-M377 < G-Y12297 (G2b1a on ISOGG).

G-M377 carriers came out of a long bottleneck, with all carrying a common paternal ancestor only around 6500 BCE, meaning that about 13,500 years of paternal cousin lineages seem not to have survived until the present. Unfortunately there are, as of this writing, no ancient skeletal remains found of a carrier of this Y-DNA haplogroup. Based on regions where it reaches peak diversity today, it seems to have originated close to it’s paternal origin among Pre-Pottery Neolithic farmers in the northern Zagros Mountains.

G-Y12297 originated with a common ancestor around 3200 BCE and includes three known lineages:

- G-M3124 (G2b1a1): A large group of men consisting of the majority of Karlani Pashtuns and one identified family of Sicilian descent, sharing an ancestor around 1800 BCE.

- G-Y12975 (G2b1a2): A large group of Ashkenazi Jews, mainly from Central and Eastern Europe, sharing a common ancestor around 850 CE. Taken into account that there were no Jews in Poland-Lithuania before the year 1350 CE, it’s likely that this common ancestor was born among the 10th century Jewish community of southern Europe, possibly medieval Italy.

- And one third group conisting of Shughni-speakers from Gorno-Badakhshan, Tajikistan, and possibly related predicted samples from Benevento and Salerno, Italy as well as Liaoning, China.

The modern spreads of the above lineages between Italy in the west and China in the east leaves an unclear geographical point of origin for this branch. Both Italy and Afghanistan have a common geographical and historical connection to Asia Minor, and it is hence quite possible that the patriarchs of these Bronze Age lineages stayed at the periphery of the northern Zagros Mountains between 3200 BCE and 1800 BCE from where they spread east and west during multiple unrelated waves of migrations.

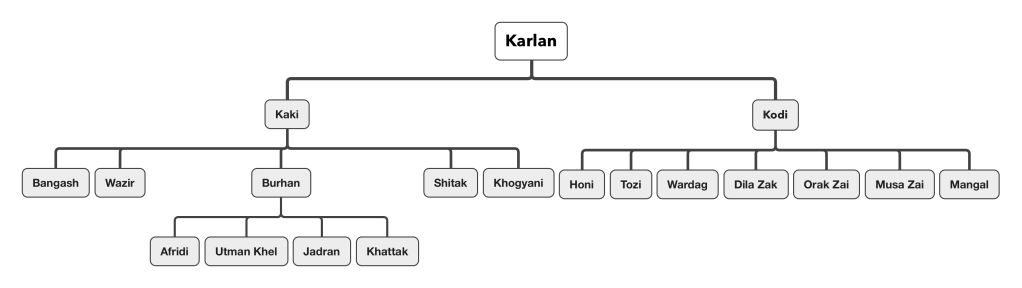

The Karlani Clade

G-M283, the so called “Karlaṇi clade”, is a Y-haplogroup shared among the vast majority of men with a common association to the Karlaṇi tribes of the Pashtuns. This lineage seems to be unique to the Karlanis, with a common ancestor currently estimated to have lived around 50 BCE.

According to their oral history, the Karlaṇi are commonly descended from a foundling named Karlaṇ. According to the Makhzan-i Afghani, compiled from oral sources in the early 1600s, the boy is said to have been found abandoned in a camping ground pot by an Ormur man named Zakariya, son of Amruddin (Makhzan-i Afghani). This tale also relates to the folk etymology of his name, kaṛi meaning “pot” and laṇi “given”. According to the tradition of the Khogyani however, the Ormur man is instead named Abdullah (Priestley, 1999). Abdullah, who was related to the Pashtun Sarban, gave the boy, who he named Karlaṇ, to his daughter in marriage, from which union the boys Kaki and Kodi were born. Thus the Karlanis are established as maternal relations both to the Ormurs (or Barak, as they are called among themselves) and the Sarbani Pashtuns, however themselves being of a different and unknown descent, which agrees with their unique Y-haplogroup.

Before the 14th century, the Karlaṇi tribes generally recall themselves as having lived as pastoralists in the hills of Parmul (modern Barmal) and Shawal, which are two valleys spanning parts of the modern Afghan province of Paktia and the modern Pakistani region of Waziristan. Details on the ancestry of Karlan varies in tradition between tribes:

- According to the Dilazak, who are recounted to have left the Shawal hills already in the 10th century, they recall that he was the biological son of a certain Sayyid Taf, an eighth generation descendant of Imam Hussain (Priestley, 1999).

- According to the Khattak, Karlaṇ was the biological son of Honi, who was from among the sons of Sarban (Priestley, 1999).

- According to Shitak (Baṇṇuchi) tradition, Karlaṇ was the son of a prince (Priestley, 1999).

While the ultimate origins of Karlaṇ is disputed, his descendants are frequently mentioned interacting with a number of groups living close to the valleys of Parmul and Shawal, namely the Farmuli (a sedentary group native to Barmal) and the Ormur (the original inhabitants east of the Shawal slopes, such as Kaniguram, Badar, Shahin and Makin).

Out of the G-M283+ samples Whole Genome Sequence (WGS) tested this far, the diversity for the branch is at it’s greatest among self-identified Karlaṇi members, who are statistically estimated to have shared a common paternal ancestor circa year 50 BCE. G-M283 currently forms its base between a lone Khattak and an unknown sample on the one hand, and all other tested samples on the other. Out of the samples tested, but a lone Wardag sample is attested to belong to the Kodi branch of the Karlaṇi, who is placed within a thousand year old cluster among Kaki samples.

Hence, testing is yet to identify an expected Y-chromosomal split between Kakis and Kodis and when this split is genetically likely to have occured. This could mean that the TMRCA (Time to Most Recent Common Ancestor) of G-M283 is expected to be pushed back to before 50 BCE. With further testing, this might indicate that the Karlaṇi existed within a cohesive tribal structure before their Pashtunisation event (see article on haplogroup R-YP1123). Results have however thus far accounted for a number of successful lineages which cross over both Kodi and Kaki tribes, namely subclade G-M3146 to which 14 out of 21 this far randomly tested individuals belong.

The Karlani Y-Tree

Advanced testing of citizen Karlaṇi researchers has thus far identified a common paternal ancestor, who the by far most living Karlaṇis share, and who lived before 50 BCE. This confirms the oral history of the Karlaṇi claiming them as adopted Pashtuns of a different paternal origin to other Pashtun tribes. That the most distantly related samples of this haplogroup self-identify as belonging to one of the modern Karlaṇi tribes, does suggest that the Karlaṇi did indeed exist as a tribal group before their adoption of the Pashto language and culture, either self-identifying as Karlaṇi in their original language, or having changed their name to Karlaṇi while keeping their tribal cohesion intact through their adoption of Pashto.

Early advanced Y-DNA testing of citizen researchers does not align smoothly with the genealogical tree of the Karlaṇi as reported in sources like the Makhzan-i Afghani and the Hayat-i Afghani. As of this writing, one early main branch of the tribe has been identified stemming from a man who was alive about 150 CE, which coincides with the height of the Kushan Empire. Future discoveries of non-Karlaṇi samples at this branches might indicate where the Karlaṇi were living at this time period. Until we find a more fitting name for this individual consistent with Karlaṇi genealogy, we have chosen to call this man “The First Elder Brother”. Tribes forming cousin branches to this man do exist, however there are currently not enough tests of modern descendants of these branches to identify a genetic cluster.

Among the descendants of The First Elder Brother we currently have two identified branches, both with patriarchs estimated to have lived around 950 CE. This period coincides with years of great turmoil in the south of the Hindukush, with the religiously motivated eastern conquests of the Saffarids in 870 CE, the retaking of the region by the Hindushahis and the Lawiks in the 890s CE, then the conquest of Zabul by Alptegin in 962 CE. Pastoral tribes of the hills like the Karlaṇi likely played a role and were strongly affected by these wars. This is likely the reason why we, despite over twenty Karlaṇis taking advanced Y-DNA tests, observe such a long bottleneck of 800 years between The First Elder Brother and his modern descendants. Whatever the circumstances, many Karlaṇi tribes founded between 150-950 CE were likely lost to wars and other difficulties up until the emergence of the Ghaznavid Empire in 977 CE, after which time wars of plunder shifted down into the Gangetic plains. The cultural effects of the Ghaznavid empire is generally believed to have been the catalyst for the mass adoption of Islam for the Afghans, who likely benefited from this new status quo. This historical period is strongly associated with multiple Y-DNA bottlenecks of living Pashtuns. This suggests that these two Karlaṇi elders of the 950 CE “The Great Elder” and Khogyani, were part of a Pashtun cultural sphere of influence, whose descendants managed to establish themselves as successful pastoral nomads with a Muslim identity in the tradition home of the Karlaṇi among the hills of Barmal and Shawal (Priestley, 1999).

Of the lower branches of the Karlaṇi Y-tree, multiple branches identified this far seem associated with elders living around 1250 CE. Scant historical evidence tells of a prevailing period of wars and drought between the 13-14th century which strongly affected the sedentary communities living south of the Hindukush. In the history of the Afghans, this period is associated with a great exodous of tribes who both in the search for new opportunity and the fleeing from conflict from amongst each other entered distant more fertile areas of habitation. Some famous examples include:

- The Bangash Karlaṇi flight from Zurmat in the 14th century, who, displaced by Ghilzais, find a new home in the Upper Kurram. This they achieve through displacing their Orakzai cousins from there by allying with the Khattak. The Bangash are to this day based in Kohat (Priestley, 1999).

- The exit of the Honi and Mangal Karlaṇi from their home in Shawal between 1250-1300 CE after coming in conflict their Karlaṇi cousins. They find their way to Baṇṇu where they’re able to establish themselves to the detrement of the local Baṇṇuchi. Around 1350 CE they are attacked by their Shitak Karlaṇi cousins, who in turn where pushed out of Shawal by the Mehsud Wazirs. The Shitak are to this day the primary population of Baṇṇu and are hence known as Baṇṇuchi, while the Honi and Mangal were pushed to the mountains west of Khost and Kurram were they are based to this day (Priestley, 1999).

- The conflict of the Lalai Wazirs and the Shitak pushed them out of the Shawal hills north towards the northern slopes of the Spin ghar. This event must have occured before the Shitak exodous of Shawal around 1350 CE. The Lalai Wazirs of Nangarhar were later in the early 17th century overrun and partly absorbed by the Khogyani Karlaṇis of Khost, who were displaced by the Ghilzais of Zurmat (Priestley, 1999).

- The great 14th century Darweshkhel and Mehsud Wazir taking of the Koh-i Kalan, now known as Waziristan. This successful conquest of the Baitani controlled Tak pass, and the Barak valleys of Baddar, Shahir, Kanigram and Makin, layed the foundation for a great growth of the Wazir Karlaṇi and the great displacement and slow decline of the once prominent Baiṭani Pashtuns and the Ormurs (Priestley, 1999).

The current Karlaṇi Y-tree hence gives further evidence for the 14th century migrations of the Karlaṇi, and additionally suggests that many of the great Karlaṇi tribes known today have their origins either in the mid-900s CE just before the Ghaznavid Islamization of the southern Hindukush or the mid-13th century wars and droughts following the Mongol invasions.

Further reading

- An summarized interview of G2b project admin Ted Kandell on Phylogeographer: https://phylogeographer.com/g-m377-diversity-across-eurasia-and-the-americas/

- Try searching for “G-M377” in the FTDNA Discover tool: https://discover.familytreedna.com/

References

- Broushaki et al. (2016) Early Neolithic genomes from the eastern Fertile Crescent. Science: Vol 353, Issue 6298. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf7943

- Lazaridis et al. (2022) Ancient DNA from Mesopotamia suggests distinct Pre-Pottery and Pottery Neolithic migrations into Anatolia. Science: Vol 377, Issue 6609. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abq0762.

- Priestley, H. (1999) Afghanistan and its Inhabitants: Translated from the HAYAT-I-AFGHANI of Muhammad Hayat Khan.

Leave a comment